-By Dr Albert Mellick

Albert Mellick is a group leader at the Ingham Institute for Applied Medical Research, and Senior research fellow, UNSW and Associate Professor, University of Sydney. His laboratory has been funded by grants from DEBRA Australia since 2018.

Dr Zlatko Kopeci (left) pictured at the EB MENA conference with EB International staff.

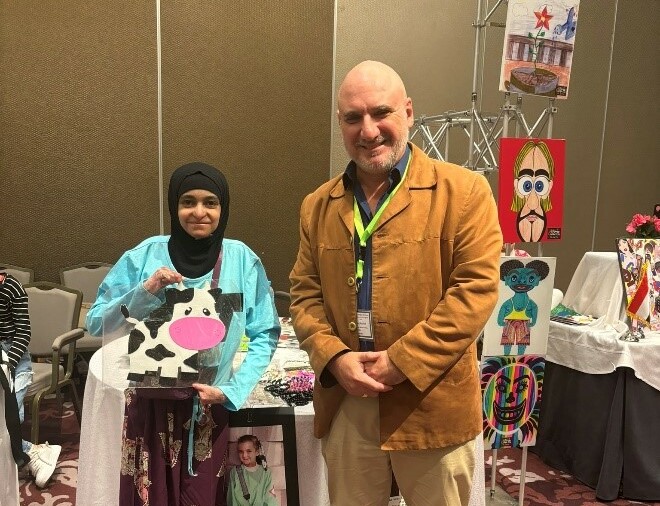

Dr Albert Mellick pictured with families inside the EB MENA conference.

When I started my journey with DEBRA Australia in 2018 it was based on an international collaboration with Austria. I am not a Dermatologist and was only vaguely aware of butterfly disease before receiving funding for the work from DEBRA Australia. Recently, it was a great privilege to attend the International EB MENA (Middle East and north Africa) meeting in Cairo and get to know the wider EB community. While many of the international speakers pulled out because of political events in the Middle East many of the families and clinicians were available to discuss both their unique circumstances and common interests. Three key things became evident. The relative lack of support for families in low- and middle-income countries, the key role of patient champions in lobbying the government, as well as the concerns of patients and their families. DEBRA Australia plays a key link in this network.

- While government support and education are important and are still lacking in Australia, it was shocking to discover the lack of government interest in places like Uganda and how families are left on their own to develop treatments and make clinical connections that will allow them to access trials.

- Hanaa El Sadat was amazing as the conference organiser. As a mother whose daughter died from complications arising from EB, and as a passionate advocate. People like Hanaa and many others in the community make our work possible and can communicate with the government more effectively than clinicians or researchers.

- Children with EB are aware for their life, for some (not all) it is the defining fact of their existence and something that if they live to a certain age are able to manage. They know no other way of living. While parents seek cures, patients are more practical. The biggest fear for RDEB young adults is amputation (which has questionable clinical outcomes) and early death from skin cancer. While high-end cures seem attractive (and may result in a world free of EB) we can’t lose focus on efforts to manage disease now. Better pain management, wound healing and early diagnostics are all practical endpoints that can be used to significantly improve quality of life.

Finally, it has become clear to me that DEBRA Australia plays a key role in linking the Australian EB community with the wider international EB world. If a cure is going to be found it will be generated through international efforts. At the same time, this strengthens local links, by showing family members and patients that they are not alone.